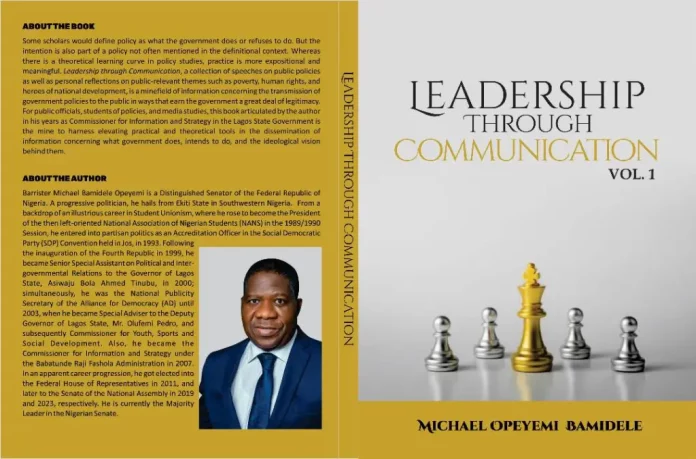

In December 2022, Mallam Salihu Lukman, a former president of the NANS that Nigerians know, turned 60. On July 25th, 2023, it was the turn of Bamidele Opeyemi, another former president of NANS of those days to turn 60. Might a layer of politicians with a definite root be emerging in Nigerian politics? That is a question for another day while we turn to this review of Senator Bamidele’s self-reporting on his stewardship by way of a book. Interestingly, it is to another NANS leader of that generation that we meet in this review. That is Sylvester Odion – Akhaine, a Professor of Political Science at the Lagos State University. Enjoy the piece!

Leadership through Communication, in two volumes, is an interesting read. It brings to the surface an intellectual problem that should deserve our attention. It raises the question of whether an individual who is a public official, in this instance, a Senator, can become a public intellectual. I shall briefly address this in what follows.

Edward Said argued in his 1993 Reith Lecture that it is difficult to draw a line between the public and private intellectual. As he puts it, “There is no such thing as a private intellectual, since the moment you set down words and then publish them you have entered the public world. Nor is there only a public intellectual, someone who exists just as a figurehead or spokesperson or symbol of a cause, movement, or position. There is always the personal inflection and the private sensibility, and those give meaning to what is being said or written.”

On his part, Paul Baran draws a line between the intellect worker comfortable with the status quo and the intellectual whose core attribute is the desire to tell the truth. In his words, “The desire to tell the truth is therefore only one condition for being an intellectual. The other is courage, readiness to carry on rational inquiry to wherever it may lead, to undertake ‘ruthless criticism of everything that exists, ruthless in the sense that the criticism will not shrink either from its own conclusions or from conflict with the powers that be.’”

In this connection, the intellectual is “a social critic, a person whose concern is to identify, to analyse, and in this way to help overcome the obstacles barring the way to the attainment of a better, more humane, and more rational social order.”

The notion of the public also needs clarification. There is the general public approximating the society as a whole, a discursive sphere with contending social classes, and the public which inheres in the officialdom “consisting of middle and upper class policy makers, administrators, and professionals…” (see Ellen Cushman, 1999). This is the sphere to which the author belongs. He has crossed into the public sphere with an overly concern for human well-being and progress while simultaneously retaining his status in officialdom. This raises some tension because he has not committed class suicide. However, class belonging is not determined by outright suicide, that is, exit from the privileged class since there are other forms of identification with the oppressed class in society. Firstly, class consciousness inclines one towards identification with the exploited in society. Secondly, practical actions to liberate the oppressed. Thirdly, class solidarity with the oppressed through shared experience. The above is the preface to understanding Leadership through Communication articulated in two volumes.

Volume One, an agglomeration of the speeches of the author while he was a Commissioner for Information and Strategy in the Lagos State government, can be divided into three parts. Firstly, it focuses on the agency of the media in promoting public policies in theory and practice. Secondly, there is a preoccupation with the downtrodden in the society. And thirdly, an evaluation of the defenders of our common good.

In furtherance of the agency of the media, especially government information agencies in national development, the author explores the role of the media from a historical perspective dating back to the anti-colonial struggle and anti-military struggle within the matrix of social responsibility. He holds the view that there is a need for synergy between government information agencies and the mainstream media in the task of nation-building through constructive criticism and feedback. The author ties this up with the importance of communication in achieving development at the grassroots, the latter being about the people. This calls for a communication strategy that combines traditional interpersonal communication methods with the modern that is both vocal, digital, and symbolic.

The author goes further to underline public relations as the engine of re-branding the nation given its negative image. Conscious of this, the Lagos State Government which he served, supported the National Institute of Public Relations and re-engineered governance in other to bring succor to the people. For him, the role of Public Relations professionals in re-branding the image of Nigeria, making it a haven for investors cannot be overemphasised.

Exploiting the ex-cathedral space given by the Young Men Christian Association, the author foregrounds the rights of man, drawing on the philosophies of the Enlightenment period, a la Rousseau and Locke, and the travails of human rights in World War I and II, and the corresponding evolution of supranational institutions for the protection of the rights of man. In this historical excursion, the author articulates Nigeria’s experience of rights violations traversing the civil war years and the last military dictatorship. Also, he acknowledges the consequent struggle of civil society to overcome violation that is at one with God’s commandment.

The subject of June 12 and the attribute of Chief Gani Fawehinmi provides the author with a reflective space to articulate the struggle for the common good of Nigeria. Nigeria’s modern history is incomplete without the mention of the place of June 12, the day in 1993, when a free and fair election was annulled by the military. Many Nigerians bore the brunt of the struggle for the realisation of the June 12 mandate. The list includes Chief M.K.O. Abiola, Pa Alfred Rewane, Alhaja Kudirat Abiola, Bagauda Kalto, and other martyrs and unsung heroes of that epic struggle. The author calls for their immortalisation.